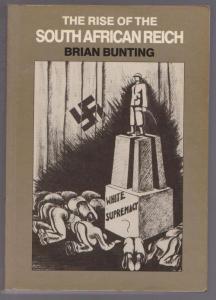

Two of the most repressive and discriminatory regimes of the 20th century were Nazi Germany and apartheid South Africa. Yet Jonathan Jansen, in Knowledge in the Blood, points out, “Apartheid is not the Holocaust, and the Holocaust is not Apartheid. These are two distinct events in their origins, content, trajectory, and outcomes.” But there are also a number of important similarities in how they became identified as, Santu Mofokeng has stated, “two of the most memorable evils which hypnotized the world,” according to Santu Mofokeng. In 2000, Patricia de Lille, a South African politician and Mayor of Cape Town, said, “South Africans had been suffering for 300 years. We can compare the suffering of the people in South Africa to the Holocaust.” She was by no means the first one to make this comparison, though. As Juliette Peires points out in her book, The Holocaust and Apartheid, “As early as 1945, the Non-European Unity Movement drew up a document that informed the United Nations of the similarities between the South African race laws and Nazism.” Brian Bunting, a South African anti-apartheid activist, made the same connection when he titled his 1964 book, The Rise of the South African Reich.

Two of the most repressive and discriminatory regimes of the 20th century were Nazi Germany and apartheid South Africa. Yet Jonathan Jansen, in Knowledge in the Blood, points out, “Apartheid is not the Holocaust, and the Holocaust is not Apartheid. These are two distinct events in their origins, content, trajectory, and outcomes.” But there are also a number of important similarities in how they became identified as, Santu Mofokeng has stated, “two of the most memorable evils which hypnotized the world,” according to Santu Mofokeng. In 2000, Patricia de Lille, a South African politician and Mayor of Cape Town, said, “South Africans had been suffering for 300 years. We can compare the suffering of the people in South Africa to the Holocaust.” She was by no means the first one to make this comparison, though. As Juliette Peires points out in her book, The Holocaust and Apartheid, “As early as 1945, the Non-European Unity Movement drew up a document that informed the United Nations of the similarities between the South African race laws and Nazism.” Brian Bunting, a South African anti-apartheid activist, made the same connection when he titled his 1964 book, The Rise of the South African Reich.

So how similar are these two regimes? And why is it important to draw certain parallels between these two regimes?

While Nazi Germany from 1933-1939 closely resembled apartheid South Africa, according to Peires, “once the war started in Europe, the actions of the German government took a path down which the apartheid government never went.”

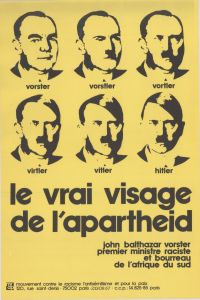

Anti-apartheid poster comparing apartheid with Nazi Germany

According to Peires, “Yes, there were strong similarities between Germany when ruled by Hitler’s Nazi Party and South Africa when ruled by the Nationalist Party. But there was a level of brutality, of sheer cruelty, depravity and inhumanity under Nazi rule completely lacking in Nationalist Party rule.”

As Peires points out, “Both the Nazi and apartheid governments employed similar means to disadvantage sections of the population that they governed. Both defined who was to be considered ‘superior’ and manipulated the lives of the ‘others,’ those deemed ‘inferior.’ They sought to preserve the pure identity of the advantaged groups and keep the rest in their designated places.”

But these two populations that were discriminated against and oppressed – the Jews in Germany and the black Africans in South Africa – were vastly different in their composition of their nation’s population. Jews were a vast minority in Germany, while black Africans were a vast majority in South Africa. In Germany in 1933, there were only 568,417 Jews in Germany out of a population of over 63 million people; therefore Jews made up less than 1% of the total population. In South Africa, the black population constituted a majority, with the 1946 census showing that they made up 79% of the country.

In Germany, while anti-Semitism had been apparent in German society for hundreds of years, Jews had gained full rights in 1871 with the formation of the nation of Germany. The new constitution at the time eliminated restrictions on Jews regarding residence, marriage, choice of professions and acquisition of real estate, and confirmed their right to vote. During the period of the Weimar Republic, between the end of the First World War and 1933, German Jews enjoyed a golden age. They were a highly visible minority in the professions, economy, and the arts. For example, 20% of Germany’s independent businessmen were Jews, 16% of all German lawyers were Jews, and before 1933, 11 out of 37 German Nobel Prize winners were Jews. They also flourished in academia, as evidenced by Albert Einstein who was a professor at Berlin’s Humboldt University. According to Peires, “In South Africa, however, black South Africans, who formed the majority population group, had never been part of white society.” According to Jonathan Jansen, author of Knowledge in the Blood, apartheid “was an institutionalized policy of racial oppression that preceded 1948 all the way back to the arrival of the colonists in the 17th century and continued as racial discrimination and economic exploitation over centuries.” Apartheid as an ideology, belief, and practice, is rooted in the arrival of Jan Van Riebeeck and the Dutch East India Company in 1652. Nancy Clark and William Worger, in South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid, state that “racial discrimination did not begin in South Africa in 1948. Indeed, it can be traced back to the beginnings of Dutch colonization of the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.” Jansen points out, “True, the practice of racial oppression was intensified through a dense architecture of racist laws and policies when the Afrikaner nationalists came to power in 1948, but in many ways it was a continuation of other forms of racial hatred and discrimination.”

As Peires points out, “When the Nazis came to power in Germany, they embarked on a program which gradually changed the position of Jews in German society from acceptance as equals to dehumanized outcasts. When the Nationalists came to power in South Africa, the blacks continued to occupy the same segregated social position that had been their lot under the former government. The apartheid system was a refinement of the discrimination that had previously been practiced.”

Primary Focus on Race

Before World War II, the Nazis used laws to curtail the activities of Jews, similar to how the apartheid government used laws to curtail the activities of so-called “non-whites.”

According to Peries, “Race played a fundamental role in determining government policy in both Nazi Germany and apartheid South Africa. Both societies used the concept of race to define and exclude certain sections of the population from enjoying full human rights…”

As Peires points out, “The South Africans were bent on safeguarding the white race. The Germans were bent on safeguarding the Aryan race.”

Hitler’s obsessive hatred of Jews led him to believe that by eliminating them and their influence “he was executing the will of God.” He was assisted in his rise to power by the Catholic Church with the 1933 Reich Concordat that Hitler signed with the Vatican. Hitler was even religiously supported by the German Christian Movement, a radical wing of German Lutheranism. These pastors believed that “Hitler was above Jesus” and by seeking to synthesize Nazi ideology and Protestant tradition, oversaw the Nazification of the Church. In South Africa, many churches tacitly condoned the discrimination and human rights abuses of black citizens. Specifically, the Dutch Reformed Church not only supported the apartheid belief of segregation of the races, but theologically justified it by arguing that the Bible supported this concept.

And to “safeguard” their race, both Nazi Germany and apartheid South Africa enacted laws to keep the races apart. In Germany, the Nuremberg Laws were passed in 1935. Part of these laws was the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, which prohibited all marriages and extramarital sex between Jews and Germans. In South Africa, legislation was also enacted aimed at preventing racial mixing. The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 and the Immorality Act of 1950 were the protective measures introduced, which included prohibiting marriages and extramarital sex between Europeans and non-Europeans.

1970s French anti-apartheid poster comparing Vorster with Hitler: “The Real Face of Apartheid”

While both regimes primarily focused the brunt of their laws, repression, ideology, and violence towards racial groups, they were not solely the victims. Besides the Jews and black Africans, both regimes showed a willingness to execute and murder others who opposed their rule. While the victims of apartheid were predominantly black, they were not exclusively so. Dr. Rick Turner and Ruth First are two examples of white activists who were killed, as was Neil Aggett who died in detention. This shows that the apartheid regime was not solely interested in killing black Africans, but anyone who opposed their belief in white supremacy. This was similar with Nazi Germany. While the vast majority of their victims were Jews, they showed time and again that they were willing to kill anyone who opposed their regime, even if they were Germans. Sophie Scholl and other members of the White Rose resistance group, despite being Germans, were executed in 1943. In 1944, in the Polish uprising known as the Warsaw Rising, hundreds of thousands of Polish citizens and insurgents (not Jews), were killed for fighting back against the Nazis.

Also, both regimes used their fear and hatred of communism to also justify their actions and oppression. Both Nazi Germany and apartheid South Africa were ardently opposed to communism and saw it as a threat to their very way of life and existence. Nazi Germany targeted communists with as much vitriol as they did Jews, including banning the German Communist Party (KPD), arresting thousands of communists and imprisoning them in concentration camps, and seeing the Soviet Union as their ultimate enemy, going to war against them from 1941-1945. In South Africa, communists were despised at an equal level. It was the Cold War and the Nationalists saw the Soviet Union as trying to bring down their government, therefore they banned the South African Communist Party, arrested thousands of communists, and even openly fought against the Soviet Union in Angola in the 1970s-80s. A number of anti-apartheid activists and organizations, including the ANC, saw the Soviet Union as the one country who would support their calls for independence and self-rule, and therefore actively sought out support, training, weapons, and money from them, including Nelson Mandela.

But race was the main ideological underpinning of National Socialism in Germany and apartheid in South Africa, and it was used to not just separate the “inferior” races, but also to slowly take away all rights and privileges accorded to citizens of a country.

Citizenship

In both Germany and South Africa, the races that were targeted for discrimination were also deprived of their citizenship. In Germany, part of the Nuremberg Laws was the Reich Citizenship Law of 1935, which stated that Jews could become citizens of the Reich. Thus Jewish Germans were summarily stripped of their citizenship. In South Africa, the Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act of 1970 removed South African citizenship from blacks. This act made blacks citizens of separate countries, the so-called “homelands” to which they were attached according to their ethnicity.

Cultural Life

In Germany, as a result of the Act of the Reich Chamber of Culture of 1933, Jews were also excluded from the cultural life of the Third Reich. They were restricted or banned from using playing fields and swimming pools, and were excluded from participating in sports at the national level. In South Africa racial separation for social, cultural and sporting activities had a long history rooted in colonialism and a formal policy of segregation even prior to apartheid. In 1953, the apartheid government passed the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act which made “mixed group” activities illegal. “Non-whites” were prohibited from attending places of entertainment where whites were present, and separate facilities had to be provided for each of the racial groups (including hospitals, buses, churches, restaurants, post offices, bathrooms, etc.). The Nationalists even segregated the beaches into white and “non-white” areas, and even had separate cemeteries. In sports, black Africans were also banned from being part of national sports teams.

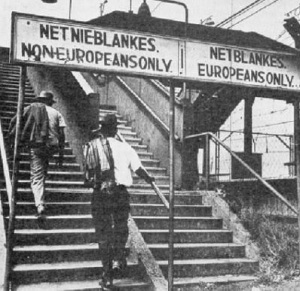

- Realities of apartheid segregation

- “Europeans Only” bench in South Africa

Employment

There were employment restrictions in both Nazi Germany and apartheid South Africa. In Germany, the 1933 Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service stated “Civil servants who are not of Aryan extraction are to be retired.” This would eventually include teachers, professors, doctors, lawyers, and other professions. In South Africa, black Africans were barred from competing for positions that were reserved for whites. The National Party that won the 1948 election endorsed the Civilized Labor Policy, originally introduced into the Public Service in 1924. Blacks who were admitted to urban areas were relegated to doing manual and unskilled labor. Positions were not given on merit, but on color.

Education

In terms of education, both restricted the opportunities for the discriminated groups to access equal educational opportunities. When Hitler became chancellor of Germany, Jewish children were receiving a comprehensive education. The 1933 Law Against the Overcrowding of German Schools and Institutions of Higher Learning, though, restricted the number of Jewish pupils in German schools. On November 15, 1938, all Jewish children still in German schools were expelled. The Reich Association of Jews in Germany created private schools for Jews, but these had to be funded by Jews themselves. The German government refused to take responsibility or to finance any Jewish educational activity. In South Africa the apartheid policy included separate schools for whites, Coloureds, Indians, and Africans. These schools were the responsibility of the government. Prior to this time, African education was conducted mainly in mission schools. While schooling became available to many more children under apartheid, the quality of education in African schools was vastly inferior to white schools. The education of African children was directed at preparing them for what was considered to be their lot in life. According to Edgar H. Brookes in Apartheid: A Documentary Study of Modern South Africa,

“Bantu education [was] a unique system – the only education system in the world designed to restrict the productivity of its pupils in the national economy to lowly and subservient tasks, to render them to non-competitive in that world…”

The Bantu Education Act of 1953 formalized the segregation of black education. As Nelson Mandela said in 1953, “The Minister of Native Affairs, Verwoerd, has been brutally clear in explaining the objects of the Bantu Education Bill. According to him the aim of this law is to teach our children that Africans are inferior to Europeans.” By 1962, expenditure per black child per year was about R12 while the expenditure per white child was R158. Eventually, the decision was implemented to even change the medium of instruction in black schools. This eliminated instruction in native languages and declared that half of the subjects would be taught in English, and the other half in Afrikaans despite that most students and teachers in these schools could write or speak Afrikaans.

Excerpt from the book, Fighting Apartheid: A Cartoon History

Media

Both used the media to their advantage and did not allow any freedom of the press. In Nazi Germany, patriotic fervor was aroused by German radio broadcasts. They not only burned books in public, but they also used newspapers, especially Die Sturmer, to faithfully publish the speeches of Hitler and support his policies. Josef Goebbels, as the Nazi propaganda minister, frequently used film as well for building up the spirit of the German people and for deriding those whom he wanted the people to despise. These films included such propaganda pieces as Triumph of the Will, which glorified Hitler and the Nazi Party, and Jew Suss, which depicted a deceitful Jew who perpetrated evil deeds. In South Africa until 1948, journalists were able to report matters as they saw fit, but with their ascension to power, the Nationalists started passing laws which eroded the freedom of the press. Rigorous censorship curbs were put in place that shackled the media. The Official Secrets Act prevented reports on information affecting the security of the state of police matters being published, and the Defense Act made it illegal to publish any information about military matters without permission. The government controlled radio and television, and no independent stations were given licenses. The state media (South African Broadcasting Corporation – SABC) had a monopoly on media in the country, serving as a mouthpiece for the National Party.

Physical Separation and Forced Removals

As Peires points out, “In both South Africa and Germany, the disadvantaged were told where they could or could not reside. In both South Africa and Germany, people were forcibly removed from their homes.”

Badges and Passes

In both Germany and South Africa, the targeted groups were forced to carry distinguishing identification. In 1941, the German Police Decree said “all Jews over the age of six are forbidden to appear in public without displaying the Jewish star.” This made it easy to monitor Jews’ movements and actions. In South Africa, blacks were required to carry “passes” at all times. The 1952 Black (Native) Laws Amendment Act specified that “all black persons, men and women, over the age of sixteen were to carry passes.” These contained full personal details including the name and address of employers, with space for the employer’s monthly signature. White South Africans did not have to carry these documents.

Ghettos and concentration camps vs. townships and bantustans

In Germany, Jews were forcibly relocated. In 1939, Reinhard Heydrich issued guidelines which included the planned formation of a “Jewish Reservation” in Lublin, Poland where Jews could be resettled. As Peires points out, “These guidelines envisaged a form of bantustan but with worse conditions.” The plan for the Lublin reservation failed, though, as did a plan to deport all Jews to Madagascar. Therefore, in 1940, Germany started to herd Jews into walled-off ghettos, of which there were 1,150 throughout Eastern Europe in Nazi-occupied territories. At the same time, thousands of concentration camps had been built for Jews and other populations, starting in 1933, that the Nazis wanted separate from their “ethnically pure” Germans. In South Africa, black Africans were relocated and restricted to homelands and townships. The 1913 Native Lands Act limited Africans, the vast majority of the population, to just 7% of the land in the country called “reserves.” As A. J. Christopher notes, “the Native Land Act was officially conceived as a first stage in drawing a permanent line between Africans and non-Africans.” Sol Plaatje, a leading voice in the black community in the early 20th century, referred to the Native Lands Act in his newspaper, Tsala ea Batho, in 1913 as “extermination” of black Africans in the country. South African President Jacob Zuma, in 2012, even referred to it as an early form of ethnic cleansing. The 1923 Native Urban Areas Act provided for towns to be segregated between the “white town” and the “black location,” or township. The Group Areas Act of 1950 divided the cities into special sections for whites, Coloureds, Asiatic/Indians and blacks. In Cape Town, for example, the Coloureds were located in places like Manenberg and Mitchells Plain. “Malays” lived in Skotches Kloof and Africans lived in Langa, Nyanga, Gugulethu, and Khayelitsha. While townships were being created in urban areas, in rural areas, black Africans were forcibly removed to “homelands,” or bantustans. In these so-called “homelands,” black Africans were attached to a specific area of the country according to their ethnicity. South Africa created 10 separate ethnic homelands for all African citizens, each based on ethnicity. These ethnic reservations included Transkei and Ciskei (for Xhosas), Bophuthatswana (for Tswana), Venda (for Venda), Gazankulu (for Tsonga), Lebowa and Qwaqwa (for Sotho), KwaZulu (for Zulu), KaNgwana (for Swazi), and KwaNdebele (for Ndebele). Starting in the 1950s, more than 3.5 million black Africans were forcibly relocated to these “homelands” during apartheid in what can only be described as ethnic cleansing. As Steve Biko stated before he was killed in prison in 1977,

“The areas where bantustans are located are the least developed in the country, often very unsuitable for agricultural or pastoral work. Not one of the bantustans have access to the sea and in all situations mineral rights are strictly reserved for the South African govt. … These tribal cocoons called ‘homelands’ are nothing else but sophisticated concentration camps where black people are allowed to ‘suffer peacefully.’”

South African “homelands” under apartheid

Collaborators

Both governments relied on using local collaborators to carry out their policies. In 1939, Reinhard Heydrich ordered that “Councils of Jewish Elders” were to be established that would be responsible for carrying out all German instructions. In ghettos, Jewish Councils were also established. The purpose of these Jewish Councils was to carry out Nazi orders regarding the Jewish population. They were responsible for supplying forced labor, registering candidates for work camps, and attending to deportations. They had to organize the food supply, manage housing, education, industry, health, police, and postal services. They were even empowered to levy taxes on the inmates of the ghetto in order to sustain these activities. In South Africa, urban blacks resided in townships separated from the white living areas, and the Urban Blacks Council Act of 1971 provided them with “self-government.” According to Peires, “The Black Local Authorities Act of 1982 was the means through which the white-dominated government sought to establish a stratum of privileged intermediaries between themselves and the blacks. It provided for the establishment of local communities, village councils and town councils for blacks in urban areas.” These so-called “black councils” had to implement government policy as opposed to being representatives of their electorate, and were therefore seen as collaborators as they had to do apartheid’s dirty work. They had to collect their own revenue, and they tried to do this by means of rent increases, which infuriated the local populations. In the “homelands,” the South African government installed leaders who would be allies and who would implement apartheid policies and support the South African government.

Forced Labor

Both used forced or slave labor, as well. In Nazi Germany, after 1938 prison labor was exploited to make profits for German companies. There were a thousands of slave labor camps in Nazi Germany and in their occupied territories. At Auschwitz alone, some 40 satellite camps were constructed near mines, foundries, and other industrial complexes. Numerous companies, like IG Farben, the world’s largest chemical and pharmaceutical company, used Jewish workers from concentration camps and directly benefited from the Holocaust. Other companies who used forced Jewish labor during the Holocaust and profited from it included BMW, Ford, General Motors, and IBM, among others. In South Africa, prison labor was also used. In Bethal in 1950, farmers were getting convicts sent from prisons to work on their farms. In just one year – 1957 – nearly a quarter of a million prisoners were sent to these farm jails as laborers. “The potato farmers had needed cheap labor, starvation labor, and the police cells and the gaols had provided a convenient reservoir,” said Helen Joseph. Some farmers were even building prisons on their farms so that they could use convicts as workers. Outside of prison labor, the South African government created a system that forced workers into the gold and diamond mines. Cheap labor and the migrant labor system with its restrictions boosted the economy, making the mines and farms more profitable than they would otherwise have been. All companies in South Africa, and those abroad who did business with South Africa, directly benefited from apartheid and the cheap labor that it offered.

Resistance

It is important to note that as well as the actions of both governments, these two regimes were similar as well due to the fact that they both faced resistance from those who they were oppressing. As Peires points out, “In both Nazi Germany and South Africa, some victims of discrimination resisted the stringent measures taken against them. The kinds of resistance undertaken ranged from passive protest to the use of force.” In Germany, while resistance had little impact on the progress of the Nazi genocidal plans, numerous attempts at resistance were made nonetheless. There were Germans who protested Nazi Germany’s oppression, included the non-violent pamphlet-writing campaign of the White Rose, led by Sophie Scholl, in 1942-43, as well as more violent resistance attempts that included plots to assassinate Hitler like the July 20th Plot in 1944. Jews also rose up in resistance to Nazi Germany. Despite being confined to brutal living conditions in the Warsaw ghetto, Jews rose up in 1943 and violently took control of the ghetto in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising that saw Jews fighting for their freedom. Even in death camps, Jews violently rose up in rebellion. In 1944, the Sonderkommando Uprising saw Jewish concentration camp inmates used explosives to blow up one of the camp’s crematoria and opened fire on the guards. Jews even formed partisan forces in the forests, fighting for survival against the Nazis. Between 20,000-30,000 Jewish partisans fought in the forests of Eastern Europe. One of the most well-known of these partisan forces was the Bielski partisans, who survived in the forests of present-day Belarus from 1941-1945. In South Africa, people also resisted apartheid in numerous ways. Non-violently, organizations formed to fight for their rights through means that included everything from letter-writing to speeches and marches to civil disobedience. The African National Congress (ANC) became one of the largest organizations as a voice of black Africans. Non-violent resistance from “non-whites” in South Africa included the Defiance Campaign of 1952, where Africans deliberately broke apartheid laws that they considered unjust, and thousands went to jail as a result. Another form of civil disobedience was the anti-pass campaign, where Africans publicly burned their passes in 1960 as a revolt against these symbols of oppression. Africans also instituted boycotts of everything from buses to white-owned businesses as a form of resistance to apartheid laws. There was also violent resistance, with the forming of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the armed wing of the ANC, in 1961. Umkhonto we Sizwe carried out acts of sabotage, which specifically targeted symbols of apartheid and the government and not people, targeting military installments, power plants, telephone lines, and transportation links. They carried out over 200 sabotage attacks on public buildings, railroad lines, and power installations from 1961-1963, and from 1977 to 1989, there were an estimated 1,500 attacks inside South Africa carried out by MK. Umkhonto we Sizwe also undertook the forming and training of a guerrilla army in exile during apartheid, which included tens of thousands of young men and women who had fled South Africa in the hopes that they would one day be able to fight and liberate their country. Other organizations also used violence to protest apartheid in South Africa, including the Azanian People’s Liberation Army (APLA), which also formed a guerrilla army in exile and carried out violent attacks inside South Africa. Both countries even saw church resistance. From a theological point-of-view, Martin Niemoller and Dietrich Bonhoeffer protested what Hitler was doing in Germany, as did Beyers Naude, Desmond Tutu, Trevor Huddleston, and many others protested what the Nationalists were doing in South Africa. In South Africa, this resistance played a vitally important role in bringing the apartheid regime to the negotiating table, whereas in Nazi Germany, it did not have the same success. As Peries points out, “Resistance by the victims of the Final Solution proved ineffectual, but resistance by those discriminated against by the apartheid system of government brought about a new constitution and a new democratic South Africa.”

Key Difference: Genocide

As Peires points out, “Except for the fact that there was torture and murder in both Nazi Germany and South Africa, here the similarities end. From 1941 Nazi Germany introduced a genocidal policy, a planned destruction of Jewish people wherever they lived. There was nothing like this in South Africa. At worst the South African apartheid government resorted to the assassination of political opponents. It did not attempt to murder an entire population group.”

“Blacks in South Africa were exploited, humiliated, and treated as second-class citizens. There was no attempt to impose anything like a Final Solution,” said Peires.

In Nazi Germany, after 1941 when the decision was taken to embark on the Final Solution, the increasingly efficient scheme for mass murder of all Jews was put in place. The Nationalists did not deliberately murder black men and women of all ages. According to Peires, “In apartheid South Africa the disadvantaged were never subjected to the treatment meted out to those relocated to German concentration camps. They sought to remove those whom they considered a threat to white supremacy. Black leaders ‘disappeared’ or were locked up for indefinite periods. Many of those detained were tortured. Many died in detention. Many were killed.” But while working and living conditions were deplorable, both in the townships and in the homelands, blacks were never deliberately worked to death or housed in quarters that were liable to cause fatal illnesses. As Peires points out, unlike Jews in German ghettoes and concentration camps,

“black South Africans were not deliberately tortured, robbed and murdered. There were many systemic deaths as a result of forced removals to areas that were inadequately sourced as far as water, arable agricultural lands and shelter were concerned. But the deaths were due not to massacres but to the insensitivity of the authorities to the hardships that accompanied the removal of families to strange destinations that were unsuitable and not prepared for their reception. The Nationalist government was not motivated by the desire to liquidate every black person in Africa but by the ideology of separate development…. To the Nazis, Jews were vermin to be eradicated. To the apartheid government, blacks were second-class citizens to be exploited.”

According to Peires,

“The final intention of the two regimes was completely different. The Nazi government wanted to rid Germany and German occupied territories of all Jews. The ‘Final Solution’ to the Jewish problem was the murder of every Jew, man, woman and child. Killing Jews, once the Second World War started, took preference over economic and even military needs. The intention of the apartheid government in South Africa was, under the guise of ‘separate development,’ to exploit ‘non-whites’ economically while separating them from the ‘whites’ in such a way that although they were in the majority, they would be in no position to challenge white power. … At no time was there ever the intention of killing the black labor force.”

Victims

One of the main differences between the two is the number of people who were killed by these regimes. While this is difficult to take into account for a number of reasons, it is worth exploring. As Peires says, “There were no similarities between the number of victims, the nature of their offenses or the method of murder.” The estimated number of Jews killed is approximately six million, which was 67% of the total Jewish population in Europe. The number of people who died in South Africa under apartheid, according to Peires, “is 36,815 including 4,024 deaths in detention or from individual killings and an estimated 10,000 systemic deaths. This constitutes about .14% of the total black population…” But others say the number of apartheid victims is much higher, especially when you take into account deaths due to forced removals, poor sanitation, lack of adequate drinking water, and lack of medical services. As Peires points out, “deaths did result from forced removals, inadequate health care, infant mortality and malnutrition. Deliberate killing only occurred as a reaction to black resistance as it developed in opposition to the discriminatory restrictions.” But you also have to take into account the apartheid-led “border wars” into the neighboring countries of Angola, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique, and Lesotho. In Tomorrow is Another Country, Allister Sparks writes that “a Commonwealth report published in 1989 estimated that South Africa’s destabilizing operations inflicted a death toll of 1.5 million on its neighbors…” These deaths are apartheid deaths as well as it was the South African government going to war in neighboring countries to maintain white supremacy. However you look at the numbers, though, numerically there is no comparison. Under the Nazis an attempt was made to murder all Jews, regardless of their status or affiliation. Most were killed en masse. Under the apartheid regime, people murdered were mainly political activists opposed to the ruling party.

Torture

According to Peires, “Both Nazi Germany and apartheid South Africa tortured victims of the system. The governments knew of the torture, they sanctioned it, they legitimized it.” In Nazi Germany, though, Jews were tortured, not for information, not for a reason, but because they were Jews. In South Africa, the victims were suspected of being enemies of the regime that ruled the country. They were not tortured solely because of their skin color. While incarcerated they were liable to be tortured, either to get them to divulge information, to confess to a crime, or simply because they were anti-apartheid activists. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) found that “the use of torture in the form of infliction of severe physical and/or mental pain and suffering for the purposes of punishment, intimidation and the extraction of information and/or confessions, was practiced systemically,” according to Peires. The TRC concluded that the South African government, as official practice, condoned the use of torture. As Alex Boraine, Deputy Chairperson of the TRC, has written: “Torture was not something that took place in a handful of prisons, performed by perverted warders. Torture was endemic.” In South Africa, though, the torture was directed at individuals, mainly those connected to opposition of the government. In Germany, the torture was often collective and directed at a group, not at an individual.

Medical and chemical experiments

In Germany, medical and chemical experiments were carried out as one facet of the program directed at the destruction of the Jews. In South Africa the military also used chemical weapons on its own people as part of their strategy to preserve a white minority rule, but they never carried out medical or chemical experiments for research. The Chemical and Biological Warfare Program, known as Project Coast, had nothing in common with the Nazi medical program. The only similarity was that both were clandestine operations conducted with the consent and encouragement of the governments of the day. Both had their own “Dr. Death” — South Africa’s Wouter Basson and Gen. Lothar Neethling and Nazi Germany’s Josef Mengele – individuals who used their medical expertise in sadistic ways to further the government’s aims. Testifying before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1997, Max du Preez even likened Neethling to Nazi geneticist Dr. Mengele. Both apartheid South Africa and Nazi Germany used diseases (in Nazi Germany – typhus, yellow fever, smallpox, and cholera; in South Africa – cholera, anthrax, E. coli, Ebola, and botulism), but the Germans used them by injecting healthy patients with these to study the effects, while in South Africa, they were used to eliminate opponents of the government. In Germany, the declared objectives were the improvement and maintenance of the superior Aryan race, and the conditions for survival of troops in wartime disasters. In South Africa the program was directed at safeguarding the apartheid South African government by destroying apartheid’s opponents.

Conclusion

As Peries points out, “The murders and deaths that resulted from apartheid cannot be labeled a genocide. Black South Africans were not targeted for extermination. … The apartheid government never considered killing their labor force. Herein lies a cardinal difference between the two systems.”

In the end, a major difference was what caused the end of these two brutal regimes. Nazi Germany was defeated on the battlefield of World War II in 1945 by the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the United States. Apartheid ended in South Africa not on the battlefield, but through the apartheid government making the conscience choice to negotiate the end of the system and usher in democracy for the first time in the country’s history. While many Nazi leaders were tried in Allied military courts like the Nuremburg courts, justice in South Africa followed a different path: the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). As Jansen points out, this is a major difference:

“In the case of the Holocaust the defeat of the Nazi state was resounding and clear. The Allies and the Soviets claimed victory, occupied the territory of the Nazis, arrested major leaders and soldiers of this racist state, set up the Nuremberg courts to try the Nazis for crimes against humanity, executed and imprisoned those found guilty, required reparations from the Germans, and subjected the defeated to a process of denazification. In the case of apartheid, the end came through a negotiated settlement in which the terms of transition favored reconciliation over recompense and peace over retribution.”

Germany and South Africa are both democratic nations today, and in both states the former oppressor and the oppressed live side by side as neighbors and countrymen now. Jews are living in Germany, and black Africans are living alongside Afrikaners in South Africa. The fact that these two brutal regimes were eventually defeated and are no longer in power is perhaps the most important and promising comparison of the two, as this shows that the hatred, fear, violence, and oppression that these regimes survived on cannot outlast the desire for independence, peace and freedom.

This is the most far fetched lying rubbish I’ve read in my entire life. Maybe you should revisit your propaganda in light of more recent legislation passed in 2012 called Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment laws in South Africa discriminating only against whites in the work place exactly the same as apartheid but in reverse and the genocide of white farmers by blacks.

Thank you for your comment. However, I must disagree. To learn more about the links between Nazi Germany and the Afrikaner Nationalists who ushered in apartheid in South Africa, I encourage you to read The Holocaust and Apartheid: A Comparison of Human Rights Abuses by Juliette Peires and A Perfect Storm: Antisemitism in South Africa, 1930-1948 by Milton Shain. Both works focus on the links between Nazi ideology and apartheid.

In reference to BEE laws in South Africa, you are viewing it through the wrong lens. Black people in South Africa have been oppressed and discriminated in every aspect of their lives for 350 years. With the advent of democracy and freedom in 1994, the only just approach to take for the new government to help rebuild the nation was to start countering the systemic racism that had permeated into every facet of life, from health care to education, housing to employment. What BEE has done is to give the most disadvantaged population in the nation (which ironically is the majority of the population) an opportunity at success. Those opportunities would not be there had it not been for BEE, so whether you call it affirmative action or BEE, these programs are vital to reversing decades (or centuries) of discrimination.

Thanks,

Craig