It was announced this week that the bastion of Afrikaner education in South Africa – Stellenbosch University – could possibly drop Afrikaans as the language of instruction and teach in English. The final say lies with the university’s council that will make a decision on November 30th.

This is a trend that is spreading throughout South African universities, as well. The University of the Free State, which currently offers classes taught in both English and Afrikaans, also is currently holding a vote as to whether courses should still be offered in Afrikaans anymore.

At the heart of this debate is how to best prepare students for a globally competitive work environment. With Afrikaans predominantly limited to being spoken in South Africa, and even then only in certain pockets of the country, the question is how much of a disservice are universities doing to these students if they are not taught in English.

“Language should be used in a way that is oriented towards engagement with knowledge in a diverse society and to ensure equitable access to learning and teaching opportunities for all students,” Stellenbosch University management said in a statement. “Since English is the common language in South Africa, all learning should be facilitated in at least English to ensure no exclusion due to language.”

Also, at issue is the cost and resources for universities like the University of the Free State to offer every course twice, once in English and once in Afrikaans.

“We are not against Afrikaans. We accepted it as an indigenous language because it was formed from African languages combined with German, [French] and Dutch,” Sechaba Dan Montsisi pointed out, one of the leaders of the 1976 uprising and an MP for more than 20 years. What students want is to feel welcomed and be able to study at one of the best universities on the continent that is in their country.

A YouTube video that was released in August started this conversation at Stellenbosch and across the nation. Entitled Luister (Afrikaans for “Listen”), it was a documentary about the lives of students of color who attend Stellenbosch who have experienced numerous incidents of racial prejudice.

The larger question is the history and identity of this language of the role it has played in South Africa’s past. The Afrikaans language is widely used in the country: it is the third most commonly spoken of South Africa’s 11 official languages, after isiZulu and isiXhosa. But it has a torrid history. It has not, two decades after the end of apartheid, shaken off its association with that system.

To the country’s Afrikaners, which amount to approximately three million people (5%) in South Africa today out of the total population of over 53 million, this language is more than just a form of communication, it is a cultural identity. To understand this, one has to explore the birth of this language.

Birth of Afrikaans

As early as 1707, ancestors of predominantly Dutch settlers in South Africa began referring to themselves as Afrikaners (the Afrikaans word for Africans), denoting their identification with the continent of Africa as their homeland. This population eventually became a diverse genetic mix of various ethnic groups and backgrounds: 34.8% Dutch, 33.7% German, 13.2% French, 7% people of color (African, Malay, etc.), 5.2% British, 3.5% unknown origin, and 2.6% other Europeans.

As a result, there was a need for a lingua franca within this diverse population. According to Leonard Thompson in A History of South Africa,

Some colonialists were holding to the Dutch of the Netherlands, the official language of the colony. Some indigenous people were still speaking their native languages. A few slaves were able to use their languages of origin, whereas Portuguese Creole had become a common means of communication among the Asian slaves. A simplified form of Dutch…with incorporated loan words from the other languages, however, was becoming the dominant lingua franca.

This was initially referred to as Cape Dutch or Kitchen Dutch, and originated as a medium of oral communication between Boer farmers and slaves. This would evolve into a distinct language – Afrikaans – and would become a touchstone of their identity.

With the arrival of the British in the early 1800s and their enforcement of English as the language of education, commerce, and civil service, many Afrikaners pushed back by entrenching their new language of Afrikaans throughout their communities.

Rev. S.J. du Toit recognized the importance of language as a powerful ethnic and cultural mobilizer. He was the prime mover of the first Afrikaans language movement, founding the first Afrikaans newspaper, Die Afrikaanse Patriot, in 1875.

In the aftermath of the Anglo-Boer War and further British imperialism, with English being enforced as the national language, Afrikaner nationalists pushed for the advancement of the Afrikaans language with a renewed fervor.

Accordingly, the first half of the twentieth century saw efforts to promote Afrikaans as a written language, its use in schools, its use in religious services, and the development of an Afrikaans press.

These movements proved successful as, by 1925, the Bible had been translated into Afrikaans, there was an Afrikaans dictionary, and there was a substantial literature in Afrikaans. That same year, a constitutional amendment replaced Dutch with Afrikaans as an official language in the country, putting Afrikaans on equal footing with English.

The National Party, comprised of Afrikaner nationalists, eventually was victorious in the 1948 election. Afrikaners, skillfully mobilized, had won political control of a country in which they formed no more than 12% of the population. With this election victory, the segregation of the past was formalized and a series of even more oppressive and rigid racial laws aimed at benefiting Afrikaners went into effect.

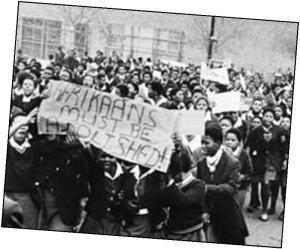

It was exactly this use of the language which sparked the 1976 student uprisings in Soweto. As part of the 1953 Bantu Education Act, the government announced the compulsory use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction from Grade 7 onwards in Math, Social Sciences, and Biology. Few black teachers knew how to speak Afrikaans, and black students regarded it as the language of the oppressor, and thus this regulation proved to be highly volatile. Thousands of students in Soweto boycotted school as a result of this language policy, leading to the Soweto Uprising in June 1976.

In many ways, it was Afrikaans that spurred the anger of the youth that marked the beginning of the end of apartheid in South Africa.

But Afrikaans was not just a language used in oppression as there were a number of Afrikaners who used the language to protest the abhorrent apartheid policies. In literature, poetry, journalism, and music, Afrikaners used the Afrikaans language to speak against what the government was doing.

In the 1960s, a group of Afrikaner writers who opposed apartheid came together in the Sestigers, which is an Afrikaans word referring to the decade that they were most influential. This literary movement was critical of apartheid, and they provided an alternative Afrikaans voice to the government to show that not all Afrikaners supported apartheid. These authors and writers included, among others, Ingrid Jonker, André Brink, and Breyten Breytenbach.

In the late 1980s, a number of Afrikaner journalists were frustrated with the media’s lack of the courage to take on the apartheid state. In November 1988, a group of anti-apartheid Afrikaans journalists, led by Max du Preez, started a new national weekly newspaper — Vrye Weekblad (Free Weekly). Their goal was to provide an alternative Afrikaans voice in the media, specifically targeting the Afrikaans-speaking population in the country. They were the only Afrikaans-language paper that exposed the murders, beatings, and corruption of the apartheid government.

The Voëlvry (“outlaw”) movement was a group of Afrikaans alternative rock musicians in the mid-1980s who used their music to rebel against the ruling National Party and traditional, conservative Afrikaner culture. They were a younger generation of Afrikaners who didn’t believe in apartheid and didn’t toe the ruling National Party line. The movement coined the term “Alternative Afrikaner” for themselves. The movement included, among others, Koos Kombuis, Johannes Kerkerroel, and Belmodus Niemand.

Today

In the past, it was the Afrikaaners expressing their desire to free themselves from the domination of British colonization and therefore from being forced to speak English.

How ironic that decades later, the headquarters of Afrikaans – Stellenbosch University – could possibly drop it for English but this time for the greater good of all South Africa’s people.

Dropping Afrikaans means that, psychologically and symbolically, the walls of apartheid are still crumbling 21 years after racial segregation was officially removed from the statute books. This is a continuing part of the decolonizing of the country that has included renaming cities and roads and taking down colonial statues from British and Afrikaner history.

Afrikaans is still one of the country’s national languages today and it is the language of 13.5% of the South African population today. So while its removal as a medium of instruction at some universities may be symbolic, it will be interesting to watch what the future holds for the world youngest language.